Klara Glosova: Every Thousand Years

Klara Glosova: Every Thousand Years

November 9 - 23, 2024

November 9 | 4-6

Klara Glosova / Every Thousand Years

Essay by T.S. Flock

“To create a little flower is the labour of ages,” is one of William Blake’s proverbs of Heaven and Hell. It came to mind in a conversation with Klara Glosova about her show “Every Thousand Years,” and not just because the collection of work assembles pieces from over a decade of work, contemplation and inquiry. The show’s title incites one to think in terms of grand scales of time, perhaps of portentous or historically significant events, and yet the subject matter is what one might call “everyday.” Blake, in his proverb, and Glosova, in her work, both remind us that we cannot take these things for granted, for we have the ability to take a curious delight in every moment if we know how to access it.

When I mentioned this proverb, Glosova quickly pulled out an irregular piece of ceramic sitting near her desk. On it, she had painted a reproduction of the title page of his Songs of Innocence and of Experience. Glosova thinks deeply, reads widely, and has consistently pushed herself out of her own comfort zone, and the result is that when she returns to “everyday” subject matter, the work she produces is infused with equal measures of erudition, intuition and compassion.

Glosova’s artistic practice began with two-dimensional work, expanded to ceramics (self-taught), and through that she returned to painting and drawing with fresh eyes and hands. Amid these ventures, Glosova added a social element to her practice, turning her own home (showers and all) into a place for other artist’s work to be displayed in open-house events and salons, and letting her evolving understanding of public-vs-private environments inform where she put her attention as an artist.

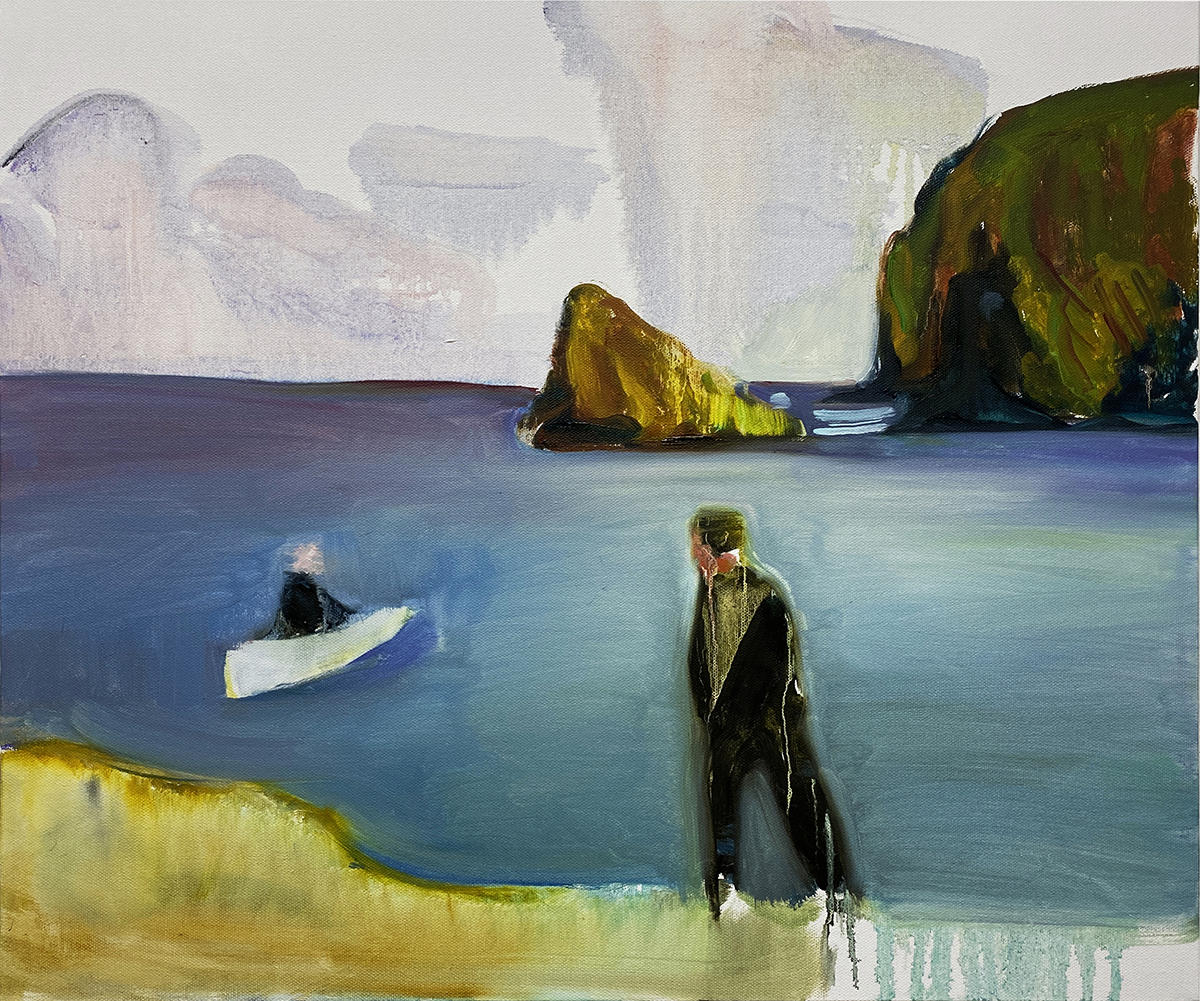

Her candid portraiture focuses on figures who are unposed, occasionally unpoised. Even in series like her “On the Sidelines” portraits of the backs of parents watching their children play soccer, we feel an intimacy with the faceless, bundled-up stranger, a camaraderie rather than voyeurism.

In works such as “Hunting Blind,” though the figure is absent, there is a human presence that is both idiosyncratic and relatable. Glosova, in her notes for “Every Thousand Years,” reflects on the cave paintings of Lascaux, those enigmatic hunting scenes made from ochre and soot over the course of centuries, ages ago. As remote as that way of life may be, we are reminded that we have always been recording life, communing, making marks and adorning our spaces. Even across that inconceivable scale of time, we remain largely the same creatures as we were in those caves. However, our specific point in history provides an entirely different perspective on our being.

The critical discourse around many well-known contemporary (male) artists who have addressed “the everyday” in their work has largely focused on some sort of detached quality in it: the loneliness of Hopper; the nihilism of Richter; the artificiality of Hockney; the ambiguity of Tuymans. Whether these assessments are definitive or not – and what they might collectively say about the preferences of art academics more broadly – is debatable, but artists and sociologists have been observing the alienating effects of industrial society, even before the hypermediated era in which we now live. We are trained to bring that sensibility to such works. Misery loves company, after all, even if the company exists only in daubs of paint on canvas.

For Glosova, a different word comes to mind: specificity. This is the specificity of the physical reality of the paintings (created with media that resist perfect control), the specificity of the objects and scenes that inspired them (which as ordinary as they might first appear can never be repeated), and the specificity of our own ability to observe, relate and interact with them.

It’s neither the animistic cyclicality of prehistory, nor the spiritual heat death of late modernity. It’s that often ignored middle path of the artist and mystic that reorients us toward curiosity and wonder. It’s the idiom at the heart of the Japanese Tea Ceremony – “Ichigo Ichie,” every encounter is once in a lifetime – reminding us of the specificity of every given moment and inviting us to experience it in its fullness with others.

Not every artist can pull this off; not every artist needs to. Glosova has come to this ability to effortlessly and faithfully capture the specificity of these moments through years of work and sincere engagement with her subject matter. To intellectualize it much further would detract from her process. Hence, I’m glad that her artist statement for this show is mostly Built to Spill lyrics and poetic musings on time and the creative act.

Not to end too quote-heavy, but to give credit where credit is due, Albert Einstein asserted that there are two ways to live one’s life: as if everything is a miracle, or nothing is. Glosova’s work quietly invites us to take the former perspective, to be bewildered, amused, perplexed by our world, and above all – even in a world of endless reproduction, and even across time spans far beyond the reckoning of the human mind – to recognize the beautiful specificity of every moment.